Wall conditioning.

A COAT OF BORON TO CAPTURE IMPURITIES.

Impurities, in the form of particles detached from materials inside the vacuum vessel, can be among a plasma’s worst enemies. Even in trace amounts, they drain energy from the plasma, degrade its performance and lead in some cases to its complete collapse. In fusion machines, contamination of the plasma by impurities is mitigated two ways: at their source by implementing specific first-wall materials and “wall conditioning,” and by preventing their penetration into the plasma through specific exhaust mechanisms such as divertors and cryopumps.

Boronization is now routine. Here, a 1991 photo of Prof. Winter (right) and colleagues ready for the final rehearsal prior to the first boronization of the US tokamak DIII-D. The implementation of diborane gas as a ”vehicle” for boron explains the protective gear.

Boron is a brittle and dark metalloid that has applications in the semiconductor and metalworking industries. During construction, ITER has used boron’s appetence for neutrons in certain concrete formulations, and research is being conducted around the world on the “ideal” aneutronic proton-boron fusion. These are not, however, the qualities that are central to the boronization process in fusion machines. What matters here, in Prof. Winter’s words, is that “boron getters oxygen like crazy.”

Coating every square millimetre of first-wall armour with boron requires a technique that resembles, in its principle, the process used for plating objects with gold, silver, chrome or other metals.

It consists in creating an electrical flow in a conductive environment, and using it to deposit particles on an object. The current originates from an electrode (an anode) with the object to be plated acting as a cathode.

In the “glow discharge” process used for boronization, anodes are used to create the electrical current flowing to the wall of the plasma chamber, which acts as a cathode. Once the magnetic field has been turned off, a gas containing boron is injected into the vacuum vessel chamber and submitted to a “very mild” electrical discharge, like in a neon light, resulting in the gas acquiring the properties of an electrically conductive plasma. The ionized particles it contains are accelerated by the electrical field and, as their molecular bonds break upon impact with the wall, boron is deposited as a perfectly homogeneous, “atomically clean” film on the wall’s surface. The technique is “easy to implement,” says Prof. Winter.

Once boronization is complete after 5 to 10 hours of continuous controlled glow discharge, particles—and particularly oxygen—are trapped under or within the boron film and cannot be released into the plasma.

Boronization creates optimal conditions for starting up plasmas. But as time passes and plasma discharges accumulate, the boron film becomes less efficient. On average, boronization is repeated every few weeks, “but if you do a good job you can significantly extend the interval between two boronizations,” according to Prof. Winter.

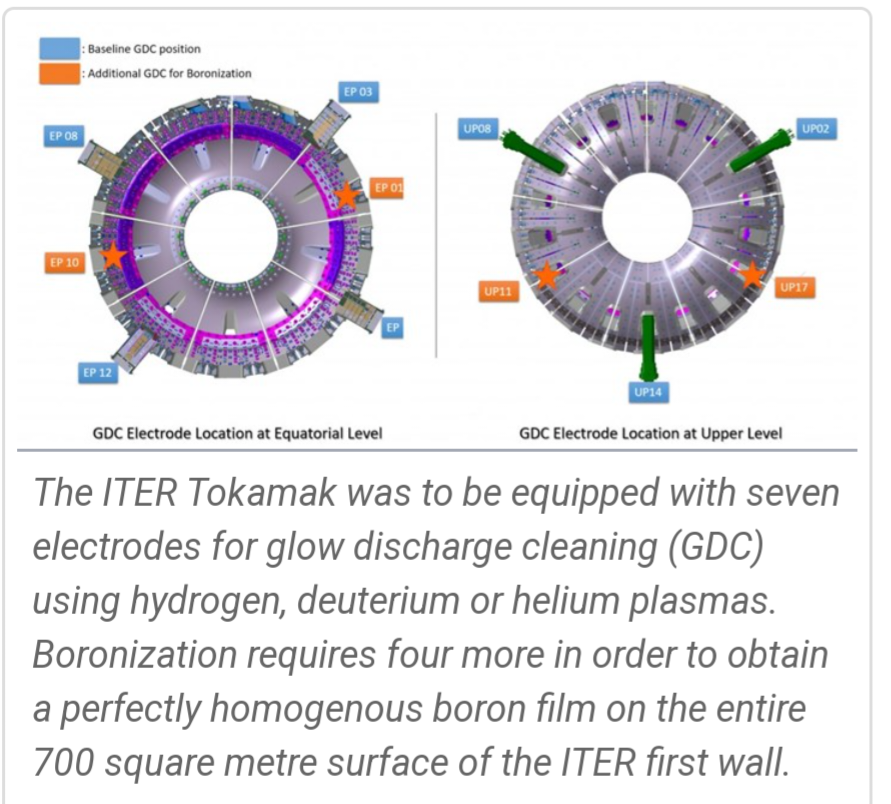

Boronization is routine—since 1991, it has been performed more than 100 times in the US tokamak DIII-D, for instance—but has never been experimented in a fusion device as large as ITER where approximately 700 square metres of first-wall surface need to be coated; there are also specific challenges when operating with deuterium-tritium plasmas. In addition, boronization requires equipping the ITER vacuum vessel with a number of additional glow discharge electrodes, dedicated fuelling lines for diborane, and specific equipment for which space availability must be identified. “The boronization recipe stands,” says Prof. Winter—but in ITER it will require a completely new set of utensils.