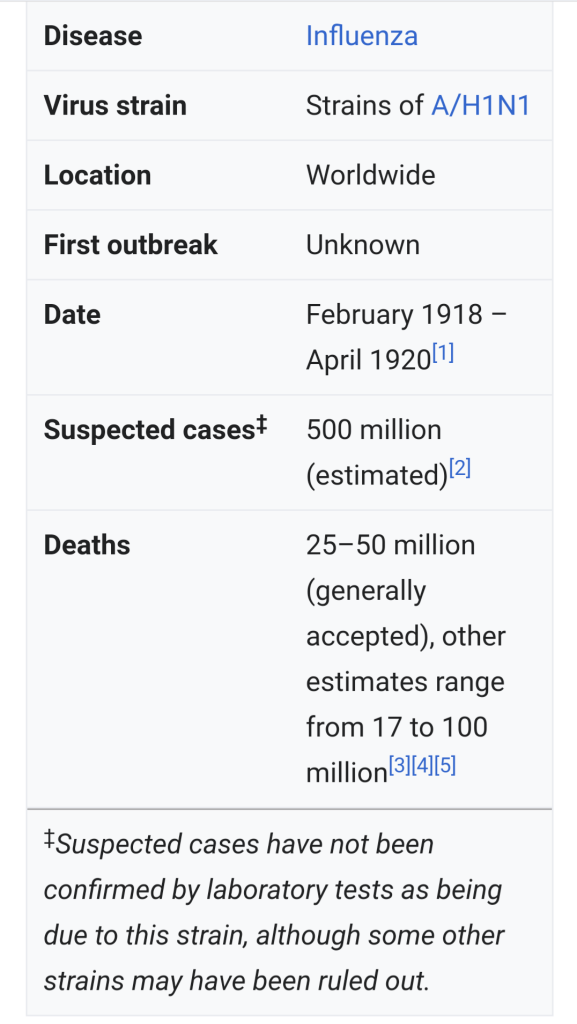

The 1918 influenza pandemic was the most severe pandemic in recent history. It was caused by an H1N1 virus with genes of avian origin. Although there is not universal consensus regarding where the virus originated, it spread worldwide during 1918-1919. In the United States, it was first identified in military personnel in spring 1918.

It is estimated that about 500 million people or one-third of the world’s population became infected with this virus. The number of deaths was estimated to be at least 50 million worldwide with about 675,000 occurring in the United States. Mortality was high in people younger than 5 years old, 20-40 years old, and 65 years and older. The high mortality in healthy people, including those in the 20-40 year age group, was a unique feature of this pandemic.

While the 1918 H1N1 virus has been synthesized and evaluated, the properties that made it so devastating are not well understood. With no vaccine to protect against influenza infection and no antibiotics to treat secondary bacterial infections that can be associated with influenza infections, control efforts worldwide were limited to non-pharmaceutical interventions such as isolation, quarantine, good personal hygiene, use of disinfectants, and limitations of public gatherings, which were applied unevenly.

The 1918 influenza pandemic, commonly known by the misnomer Spanish flu or as the Great Influenza epidemic, was an exceptionally deadly global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 influenza A virus. The earliest documented case was March 1918 in Kansas, United States, with further cases recorded in France, Germany and the United Kingdom in April.

Two years later, nearly a third of the global population, or an estimated 500 million people, had been infected in four successive waves. Estimates of deaths range from 17 million to 50 million, and possibly as high as 100 million, making it the second deadliest pandemic in human history after the Black Death bubonic plague of 1346–1353.

Emergency hospital during influenza epidemic, Camp Funston, Kansas.

Emergency hospital during influenza epidemic (NCP 1603), National Museum of Health and Medicine.

Description: Beds with patients in an emergency hospital in Camp Funston, Kansas, in the midst of the influenza epidemic. The flu struck while America was at war, and was transported across the Atlantic on troop ships.

Date: circa 1918

Photo ID: NCP 1603

Source Collection: OHA 250: New Contributed Photographs Collection, Otis Historical Archives, National Museum of Health and Medicine.

Rights: No known restrictions upon publication, physical copy retained by the National Museum of Health and Medicine. Publication and high resolution requests should be directed to NMHM (www.medicalmuseum.mil).

Date, circa 1918.

Source,, Emergency hospital during influenza epidemic (NCP 1603), National Museum of Health and Medicine. https://www.buckscountycouriertimes.com/news/20190923/mxfctter-museum-to-mark-historic-influenza-pandemic/1

Author, Otis Historical Archives, National Museum of Health and Medicine.

The pandemic occured near the end of World War I, when wartime censors suppressed bad news in the belligerent countries to maintain morale, but newspapers freely reported the outbreak in neutral Spain, creating a false impression of Spain as the epicenter and leading to the “Spanish flu” misnomer.

Limited historical epidemiological data make the pandemic’s geographic origin indeterminate, with competing hypotheses on the initial spread.

Most influenza outbreaks disproportionately kill the young and old, with a higher survival rate in-between, but this pandemic had unusually high mortality for young adults. Scientists offer several explanations for the high mortality, including a six-year climate anomaly affecting migration of disease vectors with increased likelihood of spread through bodies of water.

The virus was particularly deadly because it triggered a cytokine storm, ravaging the stronger immune system of young adults, although the viral infection was apparently no more aggressive than previous influenza strains.

Malnourishment, overcrowded medical camps and hospitals, and poor hygiene, exacerbated by the war, promoted bacterial superinfection, killing most of the victims after a typically prolonged death bed.

The 1918 Spanish flu was the first of three flu pandemics caused by H1N1 influenza A virus; the most recent one was the 2009 swine flu pandemic.

The 1977 Russian flu was also caused by H1N1 virus.

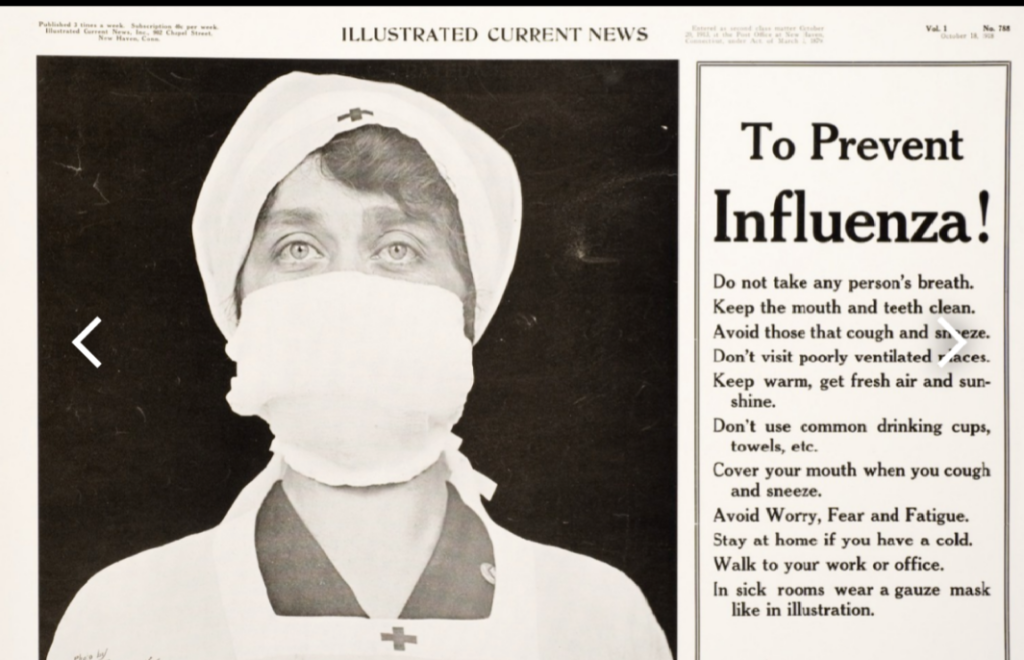

Black and white poster of a Red Cross nurse with a gauze mask over her nose and mouth.

Tex, next to the image provides public health information “To prevent influenza!” Photograph by Paul Thompson (1878 – 1940).

Published in New Haven, Conn. : Illustrated Current News, 1918.

Date1918.

Source

https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-101580385-img

Originally published in “Illustrated Current News”, New Haven, CT. Volume 1, no. 785 (or 788), 1918.

Author, Paul Thompson.

Different names.

Outbreaks of influenza-like illness were documented in 1916–17 at British military hospitals in Étaples, France, and just across the English Channel at Aldershot, England. Clinical indications in common with the 1918 pandemic included rapid symptom progression to a “dusky” heliotrope cyanosis of the face. This characteristic blue-violet cyanosis in expiring patients led to the name ‘purple death’.

The Aldershot physicians later wrote in The Lancet, “the influenza pneumococcal purulent bronchitis we and others described in 1916 and 1917 is fundamentally the same condition as the influenza of this present pandemic.”

This ‘Purulent bronchitis’ is not yet linked to the same A/H1N1 virus, but it may be a precursor.

In 1918, ‘epidemic influenza’ (Italian: influenza, influence), also known at the time as ‘the grip’ (French: la grippe, grasp), appeared in Kansas in the U.S. during late spring, and early reports from Spain began appearing on 21 May.

Reports from both places called it ‘three-day fever’ (fiebre de los tres días).

Sanitation. Influenza epidemic 1918. Symptomatology.

Date, 30 March 2013, 18:58:08

Source, https://www.flickr.com/photos/medicalmuseum/3548786222/sizes/l/in/set-72157614294614418/

Author, Otis Historical Archives nat’l Museum of Health & medicine (OTIS Archive 1).

However notwithstanding many international factors affecting our global relationships, mention to the country or countries of origin of such pandemics is not an important factor in treatment of the diseases.

Therefore mention to the country / ies of origin is being avoided in the 21st. Century and blame games are not being done, nor resorted to.

Greater stress is being made to develop and manufacture Vaccines, medicines, cures, etc. so that our world and humanity can successfully overcome pandemics.

Associative names.

Many alternative names are exonyms in the practice of making new infectious diseases seem foreign.

This pattern was observed even before the 1889–1890 pandemic, also known as the ‘Russian flu’, when the Russians already called epidemic influenza the ‘Chinese catarrh’, the Germans called it the ‘Russian pest’, while the Italians in turn called it the ‘German disease’. These epithets were re-used in the 1918 pandemic, along with new ones.

Timeline.

First wave of early 1918.

The pandemic is conventionally marked as having begun on 4 March 1918 with the recording of the case of Albert Gitchell, an army cook at Camp Funston in Kansas, United States, despite there having been cases before him. The disease had already been observed 200 miles away in Haskell County as early as January 1918, prompting local doctor Loring Miner to warn the editors of the U.S. Public Health Service’s academic journal Public Health Reports. Within days of the 4 March first case at Camp Funston, 522 men at the camp had reported sick.[88] By 11 March 1918, the virus had reached Queens, New York. Failure to take preventive measures in March/April was later criticized.

As the U.S. had entered World War I, the disease quickly spread from Camp Funston, a major training ground for troops of the American Expeditionary Forces, to other U.S. Army camps and Europe, becoming an epidemic in the Midwest, East Coast, and French ports by April 1918, and reaching the Western Front by the middle of the month. It then quickly spread to the rest of France, Great Britain, Italy, and Spain and in May reached Wrocław and Odessa. After the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (March 1918), Germany started releasing Russian prisoners of war, who then brought the disease to their country. It reached North Africa, India, and Japan in May, and soon after had likely gone around the world as there had been recorded cases in Southeast Asia in April. In June an outbreak was reported in China. After reaching Australia in July, the wave started to recede.

The first wave of the flu lasted from the first quarter of 1918 and was relatively mild. Mortality rates were not appreciably above normal, in the United States about 75,000 flu-related deaths were reported in the first six months of 1918, compared to ~63,000 deaths during the same time period in 1915. In Madrid, Spain, fewer than 1,000 people died from influenza between May and June 1918. There were no reported quarantines during the first quarter of 1918. However, the first wave caused a significant disruption in the military operations of World War I, with three-quarters of French troops, half the British forces, and over 900,000 German soldiers sick.

Seattle policemen wearing white cloth face masks during the Spanish flu pandemic, December 1918.

Deadly second wave of late 1918.

American Expeditionary Force victims of the Spanish flu at U.S. Army Camp Hospital no. 45 in Aix-les-Bains, France, in 1918

The second wave began in the second half of August 1918, probably spreading to Boston and Freetown, Sierra Leone, by ships from Brest, where it had likely arrived with American troops or French recruits for naval training. From the Boston Navy Yard and Camp Devens (later renamed Fort Devens), about 30 miles west of Boston, other U.S. military sites were soon afflicted, as were troops being transported to Europe. Helped by troop movements, it spread over the next two months to all of North America, and then to Central and South America, also reaching Brazil and the Caribbean on ships. In July 1918, the Ottoman Empire saw its first cases in some soldiers.

From Freetown, the pandemic continued to spread through West Africa along the coast, rivers, and the colonial railways, and from railheads to more remote communities, while South Africa received it in September on ships bringing back members of the South African Native Labour Corps returning from France. From there it spread around southern Africa and beyond the Zambezi, reaching Ethiopia in November. On 15 September, New York City saw its first fatality from influenza. The Philadelphia Liberty Loans Parade, held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on 28 September 1918 to promote government bonds for World War I, resulted in 12,000 deaths after a major outbreak of the illness spread among people who had attended the parade.

From Europe, the second wave swept through Russia in a southwest–northeast diagonal front, as well as being brought to Arkhangelsk by the North Russia intervention, and then spread throughout Asia following the Russian Civil War and the Trans-Siberian railway, reaching Iran (where it spread through the holy city of Mashhad), and then later India in September, as well as China and Japan in October. The celebrations of the Armistice of 11 November 1918 also caused outbreaks in Lima and Nairobi, but by December the wave was mostly over.

The second wave of the 1918 pandemic was much more deadly than the first. The first wave had resembled typical flu epidemics; those most at risk were the sick and elderly, while younger, healthier people recovered easily. October 1918 was the month with the highest fatality rate of the whole pandemic. In the United States, 292,000 deaths were reported between September–December 1918, compared to ~26,000 during the same time period in 1915. The Netherlands reported 40,000+ deaths from influenza and acute respiratory disease. Bombay reported about 15,000 deaths in a population of 1.1 million. The 1918 flu pandemic in India was especially deadly, with an estimated 12.5–20 million deaths in the last quarter of 1918 alone.

Third wave of 1919

In January 1919, a third wave of the flu hit Australia, where it killed around 12,000 people following the lifting of a maritime quarantine, and then spread quickly through Europe and the United States, where it lingered through the spring and until June 1919. It primarily affected Spain, Serbia, Mexico and Great Britain, resulting in hundreds of thousands of deaths. It was less severe than the second wave but still much more deadly than the initial first wave. In the United States, isolated outbreaks occurred in some cities including Los Angeles, New York City, Memphis, Nashville, San Francisco and St. Louis. Overall, American mortality rates were in the tens of thousands during the first six months of 1919.

Fourth wave of 1920.

In the northern hemisphere, fears of a “recurrence” of the flu grew as fall approached. Experts cited the history of past flu epidemics, such as that of 1889–1890, to predict that such a recurrence a year later was not unlikely, though not all agreed. In September, U.S. Surgeon General Rupert Blue said a return of the flu later in the year would “probably, but by no means certainly,” occur. France had readied a public information campaign before the end of the summer, and Britain began preparations in the fall with the manufacture of vaccine.

In the United States, there were “almost continuously isolated or solitary cases” of flu throughout the spring and summer months.

An increase in scattered cases became apparent as early as September, but Chicago experienced one of the first major outbreaks of the flu beginning in the middle of January. The Public Health Service announced it would take steps to “localize the epidemic”, but the disease was already causing a simultaneous outbreak in Kansas City and quickly spread outward from the center of the country in no clear direction. A few days after its first announcement, PHS issued another assuring the disease was under the control of state health authorities and an outbreak of epidemic proportions was not expected.

It became apparent within days of the start of Chicago’s explosive growth in cases that the flu was spreading in the city at an even faster rate than in winter 1919, though fewer were dying. Within a week, new cases in the city had surpassed its peak during the 1919 wave.[126] Around the same time, New York City began to see its own sudden increase in cases, and other cities around the country were soon to follow. Certain pandemic restrictions, such as the closing of schools and theaters and staggered business hours to avoid congestion, were reimposed in cities like Chicago, Memphis, and New York City. As they had during the epidemic in fall 1918, schools in New York City remained open, while those in Memphis were shuttered as part of more general restrictions on public gatherings.

Amidst the spreading outbreak, Surgeon General Blue warned the public not to get “panicky” over the flu.

Nevertheless, the Senate had sensed

a turn in the tide (as the flu began to afflict their own families) and on 27 January passed an appropriations bill for $500,000 for the study of influenza. First introduced in July 1919 by Senator Warren G. Harding after the third wave had subsided, the bill had been whittled down from $5 million. Senator William H. King of Utah fundamentally opposed the bill, criticizing PHS for the “vast autocracy” it had become; Senator James D. Phelan of California sought to have the bill recommitted to the Committee on Public Health until there was an investigation into what previous flu funding had produced, but this failed. Ultimately, a letter from Carter Glass, Secretary of the Treasury, regarding the outbreaks occurring in large cities and the threat they posed to the rest of the country persuaded many senators to vote for the package.

The fourth wave in the United States subsided as swiftly as it had appeared, reaching a peak in early February. “An epidemic of considerable proportions marked the early months of 1920”, the U.S. Mortality Statistics would later note; according to data at this time, the epidemic resulted in one third as many deaths as the 1918–1919 experience. New York City alone reported 6,374 deaths between December 1919 and April 1920, almost twice the number of the first wave in spring 1918. Other US cities including Detroit, Milwaukee, Kansas City, Minneapolis, and St. Louis were hit particularly hard, with death rates higher than all of 1918. The Territory of Hawaii experienced its peak of the pandemic in early 1920, recording 1,489 deaths from flu-related causes, compared with 615 in 1918 and 796 in 1919. Nenana, Alaska, had similarly avoided the extent of the pandemic for the previous two years, but by May 1920 an outbreak had consumed the town. Reports suggested that during the first two weeks of the month, the majority of the town’s population became infected; 10% of the population were estimated to have died.

In winter and spring 1920, a fourth wave also occurred in various areas including Switzerland, Scandinavia, Mexico, and some South American islands. Poland experienced a devastating outbreak during the winter months, with its capital Warsaw reaching a peak of 158 deaths in a single week, compared to the peak of 92 reached in December 1918; however, the 1920 epidemic passed in a matter of weeks, while the 1918–1919 wave had developed over the entire second half of 1918.

By contrast, the outbreak in western Europe was considered “benign”, with the age distribution of deaths beginning to take on that of seasonal flu. Five countries in Europe (Spain, Denmark, Finland, Germany and Switzerland) recorded a late peak between January–April 1920. Peru experienced a late wave in early 1920, and Japan had one from late 1919 to 1920, with the last cases in March.

American Red Cross nurses tend to flu patients in temporary wards set up inside Oakland Municipal Auditorium, 1918.

End of the pandemic.

By 1920, the virus that caused the pandemic evolved to become much less deadly and subsequently caused only ordinary seasonal flu.[ By 1921, deaths had returned to pre-pandemic levels.

Courtesy Wikipedia mainly, CC BY-SA 3.0 unless otherwise noted.