Pro-democracy Belarusian dissidents are conducting war games and learning how to fire a pistol and other guns in Poland. Under the watchful eye of a police officer turned private shooting instructor, recruits are preparing to join Ukraine’s resistance.

Poland has become a safe haven for many Belarusians looking to escape President Alexander Lukashenko’s Soviet-style autocracy. The long-time leader has maintained a tight grip on power since 1994.

For Belarusians, who consider Ukrainians a brethren nation, the stakes feel especially high. Russian troops have used Belarusian territory to invade Ukraine since the early days of the war, and Lukashenko has publicly stood by his long-time ally, Russian President Vladimir Putin, describing him as his “big brother.” Russia, for its part, has pumped billions of euros into Lukashenko’s state-controlled economy with cheap energy and loans.

Some of the Belarusian fighters are only passing through on their way to Ukraine, while others have remained for training.

“We taught tactics, the use of weapons during an attack, defence. In general, we started from the beginning, that is, we taught these people the basics of shooting, how to hold a weapon, how to reload, how to change magazines, how to work together as a team, and how to react to an attack or an ambush” says Dariusz Tomysek, a Polish military instructor.

Another man Vadim Prokopiev heads a unit called “Pahonia” which has been overseeing new recruits in recent days.

“This entire battalion is people who, like Vadim, are tired of Lukashenko,” says Matthew Parker, a former member of the US army who is also on site in Poland. “They hate Russia because of their interference and they see the Ukrainians as their brothers, and they say, ‘look, if we help Ukraine, and we beat the Russians, we teach our own people that you can resist.'”

Massive protests broke out on the streets of Minsk after the President won another term in the 2020 election. While the opposition say the election was fraudulent, ensuing demonstrations were met with a brutal crackdown, leading to Prokopiev’s belief that no “velvet revolution” can be expected there.

Armed with AK47s and a few dozen men per position, the fighters hope the Belarusian border will not be used by invading forces again.

“We’ll be in the frying pan,” joked Vova, a man who volunteered to fight in the Donbas in 2014 and was in the Soviet army. Vova signed up to fight alongside his brother, Ihor, and his brother’s son, Maksym, on the second day of the war.

“They took the first 500 men in the queue that day, but there were over 800 of us,” said Ihor, sat between his brother and son at the makeshift barracks near the border.

WARSAW, Poland; One is a restaurateur who fled Belarus when he learned he was about to be arrested for criticizing President Alexander Lukashenko. Another was given the choice of either denouncing fellow opposition activists or being jailed. And one is certain his brother was killed by the country’s security forces.

What united them is their determination to resist Lukashenko by fighting against Russian forces in Ukraine.

Belarusians are among those who have answered a call by Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy for foreign fighters to go to Ukraine and join the International Legion for the Territorial Defense of Ukraine, given the high stakes in a conflict which many see as a battle pitting dictatorship against freedom.

For the Belarusians, who consider Ukrainians a brethren nation, the stakes feel especially high.

Russian troops used Belarusian territory to invade Ukraine early in the war, and Lukashenko has publicly stood by longtime ally, Russian President Vladimir Putin, describing him as his “big brother.” Russia, for its part, has pumped billions of dollars into shoring up Lukashenko’s Soviet-style, state-controlled economy with cheap energy and loans.

Weakening Putin, the Belarusian volunteers believe, would also weaken Lukashenko, who has held power since 1994, and create an opening to topple his oppressive government and bring democratic change to the nation of nearly 10 million.

For many of the Belarusians, their base is Poland, a country on NATO’s eastern flank that borders Belarus and Ukraine and which has become a haven for pro-democracy Belarusian dissidents before becoming one for war refugees from Ukraine.

Some of the volunteer fighters are already in Poland, and some only pass through briefly on their way to Ukraine.

“We understand that it’s a long journey to free Belarus and the journey starts in Ukraine,” said Vadim Prokopiev, a 50-year-old businessman who used to run restaurants in Minsk. He fled the country after a rumor spread that he would be arrested for saying publicly that the government wasn’t doing enough for small businesses.

“When the Ukraine war will be eventually over, our war will just start. It is impossible to free the country of Belarus without driving Putin’s fascist troops out of Ukraine,” he said.

Prokopiev heads a unit called “Pahonia” that has been training recruits. They were being trained by a Polish ex-police officer who is now a private shooting instructor.

Prokopiev wants his men to gain critical battle experience, and he hopes that one day soon a window of opportunity will open for democratic change in Belarus. But he says it will require fighters like himself to be prepared, and for members of the security forces in Belarus to turn against Lukashenko.

“Power from Lukashenko can only be taken by force,” he said.

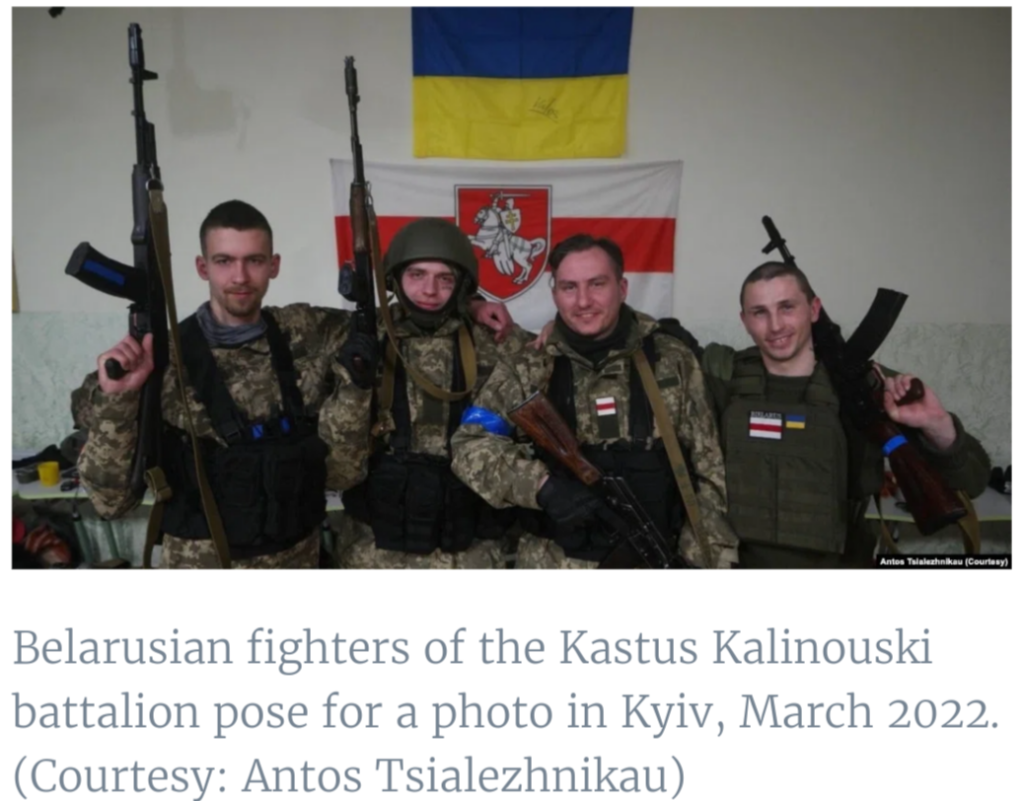

On Saturday, men with another unit, Kastus Kalinouski, gathered in Warsaw in the Belarus House, where sleeping bags, mats and other Ukraine-bound equipment were piled high. They sat together, talking and snacking on chocolate and coffee as they prepared to deploy to Ukraine later in the day. Most didn’t want to be interviewed out of concerns for their security and that of family back home.

The regiment, formally part of Ukraine’s armed forces, was named after the leader of an anti-Russian insurrection in the 19th century who is viewed as a national hero in Belarus.

Lukashenko has called them “crazy Belarusian citizens,” and authorities have put 50 members of Kastus Kalinouski on a wanted list and initiated criminal cases against them.

One willing to describe his motivations was a 19-year-old, Ales, who has lived in Poland since last year. He fled Belarus after the country’s security service, which is still called the KGB, detained him and forced him to denounce an anti-Lukashenko resistance group in a video. He was told he would be jailed if he didn’t comply.

Dressed all in black from a hooded sweatshirt to his boots, he admitted to feeling nervous as the moment arrived to head into Ukraine. He had never received any military training, but would get it once he arrived in Ukraine. But just how much, and where he would be deployed, he didn’t yet know.

He said he was going to fight not only to help Ukraine “but to make Belarus independent.” He said it was also important for him that people realize that the Belarusian people are very different from the Lukashenko government.

It is a dangerous mission. At least four volunteers from the Kastus Kalinouski unit have already died. A deputy commander, Aliaksiej Skoblia, was killed in a Russian ambush near Kyiv and was later recognized by Zelenskyy as a Hero of Ukraine.

Still, the fighting in Ukraine can feel less dangerous at times than seeking to resist Lukashenko at home, where many activists are in prison facing harsh conditions.

Organizing the Kastus Kalinouski recruits was Pavel Kukhta, a 24-year-old who already fought in Ukraine’s Donbas region in 2016, suffering burns and the loss of most of hearing in one ear. Kukhta said his half-brother, Nikita Krivtsov, was found dead by hanging in a wooded area outside Minsk in 2020. Police said there was no evidence of foul play but Kukhta says he and the rest of the family are certain Krivtsov was killed for joining the anti-Lukashenko protests. But he insisted that his support for Ukraine is not about revenge, only about fighting for democratic change.

“If Putin is defeated, Lukashenko will be defeated,” he said.

New details have emerged about Belarusians fighting for Ukraine against Russia’s invasion as part of a broader struggle to free their own country from Russian domination and the rule of Moscow-backed autocrat Alexander Lukashenko.

The deputy commander of the largest pro-Ukraine Belarusian fighting force said its numbers have almost reached the size of an average Ukrainian battalion, which he said has about 450-500 troops.

“Several thousand more have applied to join us through our online recruitment tool,” said Vadim Kabanchuk of the Kastus Kalinouski battalion, named after a Belarusian revolutionary who led a regional uprising against Russian occupation in the 1860s.

The Kalinouski battalion began forming in Kyiv after Russia had begun its full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24. The battalion uses the Telegram channel @belwarriors to share news and images of its activities. On March 9, it announced its adoption of the Kalinouski name in a video posted to the platform.

Kabanchuk said he is one of a number of the Belarusian battalion’s fighters who have been active in Ukraine’s defense starting in 2014. That year, Russian forces invaded eastern Ukraine’s Donbas region to foment a separatist uprising within its Russian-speaking community.

Belarusians have been drawn to fight for Ukraine for years in the hope that freeing it from Russian occupation would boost their own efforts to rid Belarus of Moscow’s influence and end the 27-year presidency of Lukashenko, a key Russian ally.

The Kalinouski battalion swore an oath of allegiance to Belarus and Ukraine in a Telegram video posted March 25. Four days later, in another video, battalion members said they had a new status as part of the Ukrainian Armed Forces and held up green booklets that resembled Ukrainian military IDs.

There has been no confirmation of the Kalinouski battalion’s announcement on websites run by the Ukrainian government and military.

Franak Viacorka, a senior adviser to exiled Belarusian opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, said that he believes the Kalinouski battalion’s declared integration into the Ukrainian Armed Forces is credible. He described the battalion as the biggest and “perhaps best organized” of the Belarusian groups fighting for Ukraine and said it has earned a right to display Belarus’ national flag and coat of arms in its operations.

“As of now, they will be fighting not only in one place, not only in defense of Kyiv, but all over Ukraine,” Viacorka said.

As Russia’s full-scale invasion began, Belarusian fighters of what later became the Kalinouski battalion joined the Ukrainian military’s volunteer Territorial Defense Force units in Kyiv, according to deputy commander Kabanchuk. The Kyiv Independent news site had reported in January that the Territorial Defense Force units would comprise former active-duty Ukrainian military personnel and other volunteers, including civilians.

Kabanchuk said some of the Kyiv territorial defense units that his fellow Belarusian fighters joined included Ukrainian fighters with ties to the Azov regiment of the Ukrainian National Guard. The Azov regiment is known for the far-right beliefs of some of its members and has been most active in Mariupol, the southern Ukrainian port besieged by Russia for weeks.

“We initially were part of Kyiv territorial defense units whose members called themselves part of the ‘Azov movement,'” said Kabanchuk. “But we are not part of the Ukrainian National Guard’s Azov regiment and don’t want to be confused with it,” he added.

Most Belarusians who volunteer to fight for Ukraine are driven not by far-right ideology but by a belief that Kyiv’s struggle is part of their own fight to free Belarus from Russian imperialism, said former Belarusian Foreign Ministry official Pavel Slunkin.

“They include bloggers, journalists, I.T. specialists, factory workers. All kinds of professions. And they want to see Belarus as a democratic state,” said Slunkin, now an analyst at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

Not all Belarusians who seek to join the Kalinouski battalion will make it through a multistage vetting process aimed at weeding out security threats, Kabanchuk explained. Those threats include the possibility of Lukashenko’s agents trying to infiltrate the battalion, he said.

“Many of the thousands who applied will be rejected after in-person interviews at the Belarusian recruitment center in the Polish capital, Warsaw, which acts as a first-stage filtration hub for potential fighters,” Kabanchuk said. “Others will be rejected as unsuitable after they arrive to the battalion bases.”

Smaller groups of Belarusian fighters have been active in other parts of Ukraine in recent weeks, according to Belarusian opposition figures. In a Thursday tweet, Tsikhanouskaya said a recently formed regiment called Pahonia is training new volunteers on behalf of Ukraine’s armed forces.

A spokesperson for the International Legion for the Defense of Ukraine, Norwegian-born Damien Magrou, responded to a question about Pahonia by saying Ukrainian officials are considering an initiative to integrate “suitable” Belarusian volunteers into the legion.

Kabanchuk said the Kalinouski battalion prefers not to join the international legion because his fighters have much more autonomy as a separate unit.

Viacorka, the Tsikhanouskaya adviser, said in a Thursday tweet that he hopes the Pahonia regiment will form the basis of a new professional Belarusian army in a post-Lukashenko era.

Lukashenko derided the pro-Ukraine Belarusian fighters last month, telling a government meeting that the fighters are “crazy” and motivated only by money.

As for his own troops, he has avoided sending them into Ukraine to join in Russia’s invasion.

Kabanchuk said that if Lukashenko were to do that, some of the Belarusian military’s forces would surrender, and others would turn against the Belarusian autocrat.

“He understands very well that sending troops into Ukraine will speed up the fall of his regime,” Kabanchuk said.