September 16. 2023 September 10. 2021.

Months of excessive heat and drought parched the Mississippi River in the summer and early fall of 2023. In September, low water levels limited barge shipments downriver and threatened drinking water supplies in some Louisiana communities, according to the Associated Press.

Water levels were especially low near Memphis, Tennessee. The images above show the Mississippi River near Memphis on September 16, 2023 (left), compared to September 10, 2021 (right). The river was significantly slimmed down in 2023, exposing some of the river bottom.

This is the second year in a row drought has caused the river to fall to near-record lows at many gauges. On September 26, 2023, the river level at a gauge in Memphis was -10.26 feet, close to the record low level, -10.81 feet, measured at the same place on October 21, 2022. That was the lowest level recorded there since the start of National Weather Service records in 1954. Water levels, or “gauge heights,” do not indicate the depth of a stream; rather, they are measured with respect to a chosen reference point. That is why some gauge height measurements are negative.

Farther upstream, water levels at New Madrid, Missouri, have been around -5 feet—near the minimum operating level—since early September 2023. Water levels on the Mississippi normally decline in the fall and winter, and in 2022, the river did not get that low until mid-October.

A hot, dry summer is the main reason water levels dropped so low in 2023. Across the globe, temperatures in summer 2023 were 1.2°C (2.1°F) warmer than average. In the U.S., Louisiana and Mississippi experienced their hottest Augusts on record, according to NOAA.

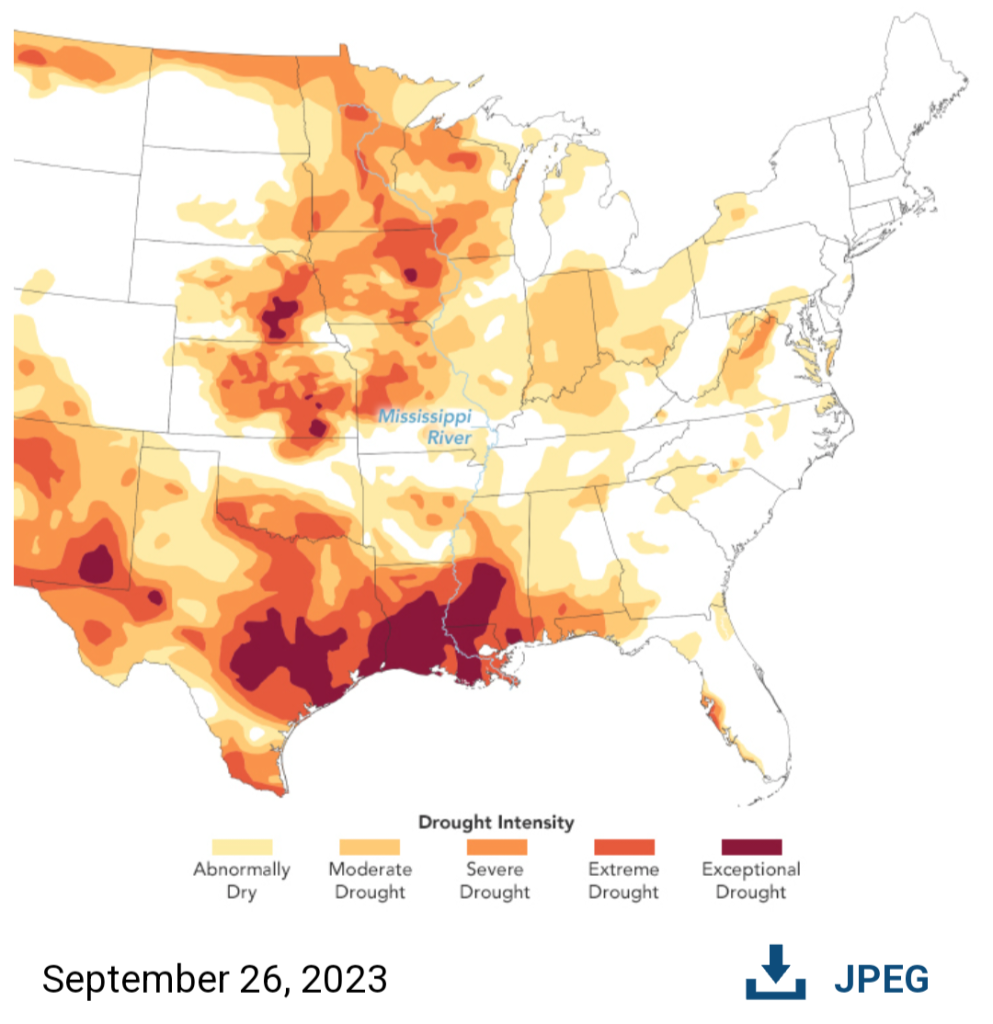

The U.S. Drought Monitor map above—the product of a partnership between the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln—shows conditions during the week of September 20-26, 2023. The map depicts drought intensity in progressive shades of orange to red. It is based on an analysis of climate, soil, and water condition measurements from more than 350 federal, state, and local observers around the country. NASA contributes measurements and models that aid the drought monitoring effort.

During that week, about 38 percent of the contiguous U.S. was experiencing drought. Lack of precipitation and high temperatures over several months severely dried out soils in states along the Mississippi River Valley. The Drought Monitor reported that 80 percent of soils in Louisiana were dry (short or very short on water) as of September 24. And for most states in the river valley, over 50 percent of topsoil was dry or very dry.

Shallow conditions along the river interrupted normal shipments of goods. According to the Associated Press, barge companies reduced the weight carried in many shipments in September because the river was not deep enough to accommodate their normal weight. Much of U.S. grain exports are transported down the Mississippi, and according to AP, the cost of these shipments from St. Louis southward has risen 77 percent above the three-year average.

The lack of freshwater flowing into the Gulf of Mexico has also allowed saltwater to make its way up the river and into some water treatment plants in southern Louisiana, according to the Associated Press. Some parts of Plaquemines Parish are under drinking water advisories and have relied on bottled water for cooking and drinking since June.

Significant rainfall would be needed to flush out saltwater in the river in Plaquemines. According to the National Weather Service’s Lower Mississippi River Forecast Center, the forecast does not look promising. If enough rainfall doesn’t arrive before mid-to-late October, saltwater could make its way to New Orleans.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey and data from the United States Drought Monitor at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Story by Emily Cassidy.

Source, NASA.