February 26, 2024.

Huge, thick ice sheets blanket much of the Antarctic continent. Amid all this ice, numerous volcanoes dot the landscape. Many are partially buried, with only their tops exposed above the ice sheet’s surface—that is, except for Mount Siple. This stately island volcano stands in full view, from sea level to its summit elevation of more than 3,100 meters (10,000 feet).

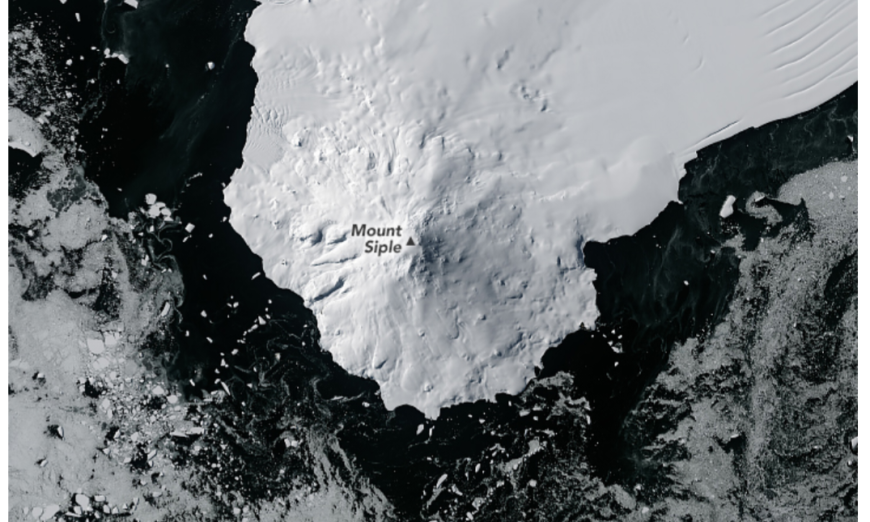

The OLI-2 (Operational Land Imager-2) on Landsat 9 captured this image of Mount Siple on February 26, 2024. Sunlight reflects from the snowy, icy surfaces, including the Getz Ice Shelf, which separates the volcano from mainland West Antarctica.

Mount Siple and other Antarctic volcanoes are located in a remote, extreme environment, making them a challenge for scientists to study and monitor. However, remote sensing can help. During the dark winter months, satellite sensors cannot collect the light needed for natural-color images like the one above, but there are other ways to “see” in the dark.

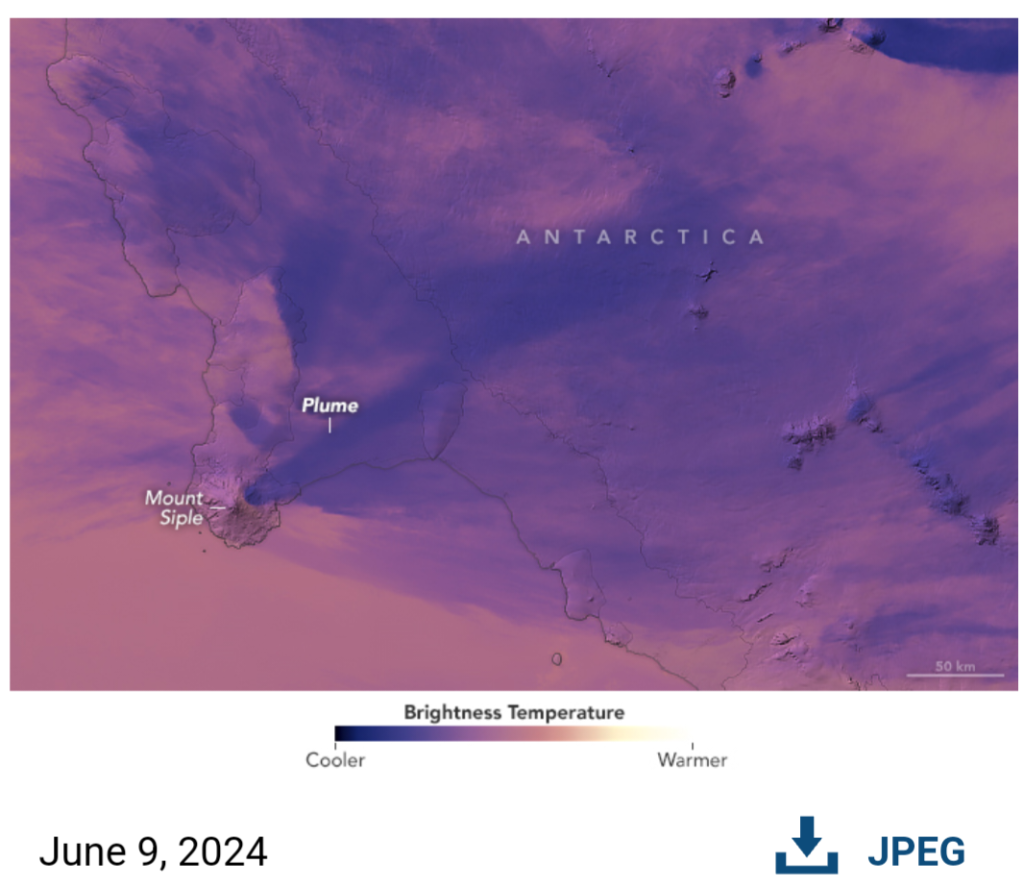

This false-color image was acquired by the VIIRS (Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite) on the Suomi NPP satellite. It shows a wider view of Mount Siple and mainland Antarctica on June 9, 2024, during the Antarctic winter. The image was overlaid on data from the Reference Elevation Model of Antarctica (REMA) to give a sense of the topography.

The colors in this image represent brightness temperature, which is useful for distinguishing the relative warmth (orange and pink) or coolness (purple and blue) of various features. Here, clouds appear cooler than the underlying icy surfaces.

Notice the plume streaming inland from near the summit of Mount Siple. The shape of the feature and its relative coolness compared to its surroundings resemble those of a volcanic plume. But according to Simon Carn, a volcanologist at Michigan Tech, it is more likely an orographic cloud. This cloud type forms when the shape of the landscape forces moist air up to altitudes where the water vapor cools and condenses. Carn notes that other satellite data show no indication of sulfur dioxide or ash in the plume. Nor is there a heat signal that would indicate hot volcanic material at or near the summit.

“The absence of all these features, and also the fact that similar features are often seen downwind of other non-volcanic topographic prominences in the Antarctic and Arctic, indicates that the plume is most likely orographically generated,” Carn said. “This is also consistent with the plume being ‘detached’ from (slightly downwind of) the volcano summit.”

Speculation about volcanic activity at Mount Siple has occurred in the past, including observations of a possible volcanic plume in 1988. That plume was later determined to be the result of atmospheric effects, according to a report from the Smithsonian Institution’s Global Volcanism Program. Researchers noted in a 2021 publication that limited observations have prevented detailed interpretations of Mount Siple’s volcanic history, writing: “At this stage, there is no indication that Mount Siple should be considered ‘active’.”

NASA Earth Observatory images by Michala Garrison, using VIIRS data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE, GIBS/Worldview, and the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership, Reference Elevation Model of Antarctica (REMA) data from the Polar Geospatial Center at the University of Minnesota, and Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Story by Kathryn Hansen.

Source, NASA.