December 28, 2024.

Bloom season, already underway for several months, continued to dazzle in the productive South Atlantic waters off Argentina. Earlier, in austral spring 2024, satellites captured a clear image of a sizeable phytoplankton bloom along the Patagonian Shelf. Communities of the tiny aquatic organisms persisted into the long days of the Southern Hemisphere summer, painting surface waters in shades of green and blue into late December.

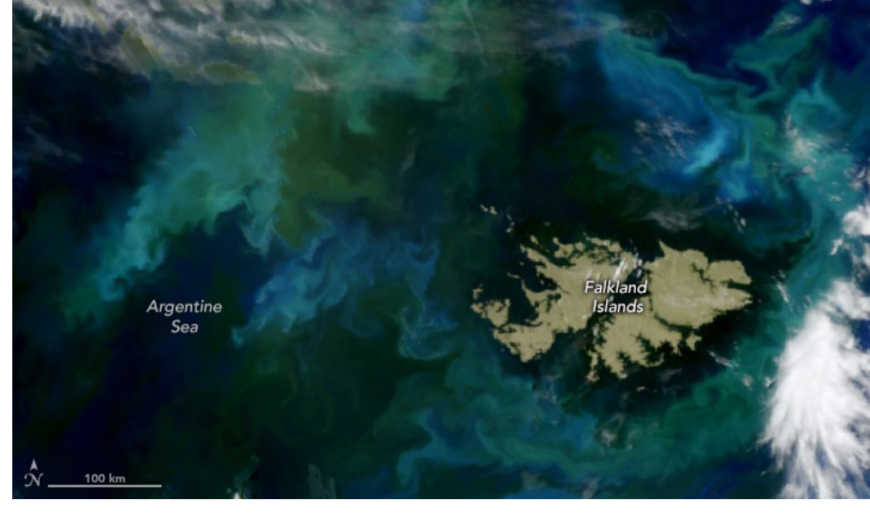

The OCI (Ocean Color Instrument) on NASA’s PACE (Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, ocean Ecosystem) satellite acquired this image of the bloom and its intricate swirls around the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas) on December 28, 2024. In the waters of the Patagonian Shelf-break front, airborne dust from the land, iron-rich currents, and upwelling from the depths provide abundant nutrients for phytoplankton. These floating sunlight harvesters support rich aquatic diversity and productive fisheries.

The various colors visible in the image likely reflect a mix of phytoplankton communities. The proportions of these communities change throughout the months-long bloom based on nutrient availability and other environmental factors. In this scene, chlorophyll-rich diatoms and other phytoplankton types that color the water green may be giving way to coccolithophores, said Ivona Cetinić, an oceanographer at Morgan State University and member of NASA’s Ocean Ecology lab.

“Coccolithophores love long days and lots of sunshine, so they are probably dominating now,” she said. Armored with plates of highly reflective calcium carbonate, these organisms make surface waters appear a milky turquoise-blue. The coccolithophore bloom that emerges each year off Patagonia is part of the so-called Great Calcite Belt. Stretching around the planet in southern waters, the region is thought to play a major role in the planet’s carbon cycle.

The distribution of colors in the image also reveals complexities in the ocean’s surface waters. “Plankton cannot swim against currents,” Cetinić said, “so the different stripes of color indicate many different water masses containing different levels of elements needed for the growth of different phytoplankton types.”

It remains a longstanding challenge to identify what types of phytoplankton are present in a bloom using remote sensing imagery alone. But scientists are getting closer thanks to the hyperspectral (fine wavelength resolution) data acquired by the PACE satellite. Cetinić and colleagues have developed a tool that enabled them to distinguish three different phytoplankton communities based on hyperspectral signatures. The scientists find the method promising but note that it is still under development. Monitoring phytoplankton on a global scale using daily observations by PACE may help scientists and resource managers monitor fisheries health, track harmful algal blooms, and identify changes in the marine environment.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Wanmei Liang, using PACE data from NASA EOSDIS LANCE and GIBS/Worldview. Story by Lindsey Doermann.

Source, NASA.